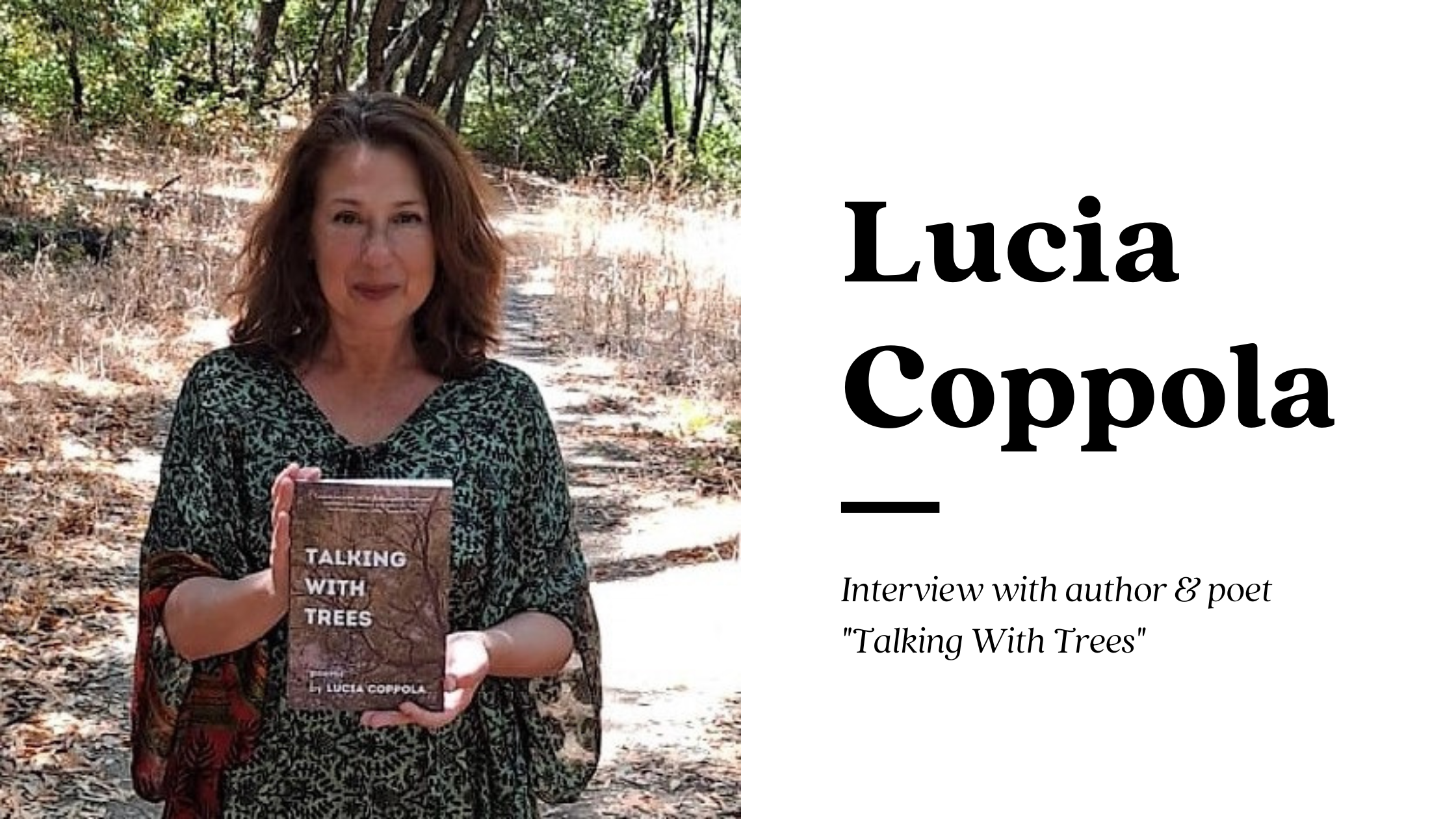

Welcome to our latest blog post, where we have the pleasure of interviewing Lucia Coppola, the author and poet of the recently published book "Talking With Trees". In this book, Lucia takes readers on a magical journey into the garden, where the extraordinary adventure of ordinary things awaits.

Through illuminating poetry and enchanting photography, Lucia weaves a tale that bridges the human and plant worlds, inviting readers to venture and explore the beauty and wisdom of nature.

In this interview, we delve deeper into Lucia's inspiration behind the book, her process of weaving poetry and photography together, and how she hopes readers will be impacted by her work. So, without further ado, let's begin the interview with Lucia Coppola.

1. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind your book "Talking With Trees"?

I love this question because it brings me back to a very special time in my life. There was a lot of prayer and meditation, walking in the forest and planting in my garden. My children were growing, and I felt tremendous love. It was almost overwhelming. I was making spiritual connections in a different way than I had done before. I began to understand “love” as a singular principle connecting all that is “good”, and I saw that nature played a huge part in this picture. So during this time, the “environment” took on a particular meaning for me. My home and its surrounding greenery became not just a background to my story but the essence of what I was living.

It’s funny because thinking about inspiration makes me think of when I was in college, where I studied a lot of religion and philosophy. I wrote my senior paper on “The Divine Comedy”. Dante’s poem, which was written at the beginning of the 14th century, begins with the lines: “Midway upon the journey of our life/ I found myself in a dark forest,/For the straightforward pathway had been lost.” The pathway in the dark forest is such a potent symbol because we are creatures of the forest. Years after college, I was walking regularly in the magnificent forest where I lived in France, and I understood that I was connecting with something much greater than myself, but also in that personal and intimate way that Dante speaks of : I, too, “found myself in a dark forest,” and I began to seek out those spaces that were full of light. I felt I needed to document that journey.

“…Not a religion,

just a tree – a companion we look in on,

an elder of the community and witness to our words – a tree

that filters the daily din and bids us to come and curl up,

to breathe, to lean steadfast into day

with a sense of destination…”

From The Oak Tree, “Talking With Trees”

In fact, there were many sources of inspiration. There are many poets, but I also remember reading Annie Dillard, “A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek” around that time. This is a contemporary piece of journal writing, but again, it made me want to begin writing things down.

2. How do you believe nature speaks to the imagination?

I always go back to the realization that the environment is not an abstract concept. It’s as much a part of us as we are of it. Just looking at a rainbow - it feels as if everything is there. But as we get out of touch with the natural world, our lives become increasingly monotone. There’s a wonderful poem by Gwendolyne Brooks that talks about the need for color particularly when we get stuck in a poor urban setting: “Kitchenette Building” begins:

“…We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. “Dream” makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like “rent,” “feeding a wife,” “satisfying a man…”

From Kitchenette Building, Gwendolyn Brooks

Thinking about the richness of nature makes me realize why there was such vehemence in the writing of romantic poets. It’s only more recently that I’ve understood that they were “romantic” because they were already in their own time nostalgic about, and paying homage to, a natural world that in the 19th century was beginning to disappear.

I recently read Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” and was struck by the degree to which, in 1817, she had already so brilliantly seen the threats that modern science and industrialization would pose to our very ancient rural customs and lifestyles. The presence of nature, its destruction, the loss of beauty and harmony…in these themes, I’ve come to see a parallel with ourselves. For me, the connection to the natural world is what makes me feel alive precisely because it gives meaning to my place in this world. I am always yearning for that connection, and I dread its loss. “The Bridge” is very much about that need :

“...She digs down in silt and mud

scratches roots for dance and tunes

words and sometimes flowers that appear

in clusters with the moon…”

From The Bridge, “Talking With Trees”

Here, I’m writing here about a character who finds it challenging to be part of the modern world while trying to preserve the vitality of existing in nature.

3. Can you talk about the process of weaving poetry and photography together in the book?

There was much taking of photos during the summer that I was writing, and I had never really done this before. This is one way in which “the digital age” has been a gift. Before, I never took photos because I find “equipment”, generally speaking, to be a nuisance. But back in 2009, I began to love having my mobile phone with me and often recorded images as I went about my usual walks and throughout the day. Taking photos became part of what I called “research”.

I still do a lot of research as I’m thinking about themes or ideas. Taking photos is a very satisfying and easy way to document fleeting thoughts and images. Some photos found their way into the book, but there were many others. Some of these other ones are on my Instagram page now.

I love the little cherubs, particularly as they actually did inspire the poem “Riddle” and became so alive in that moment. This was the first poem in the collection that I wrote, from the start, as a poem.

“…I suppose Heaven and Hell must be here in this place

where the paths are so straight and perplexing.

And I wonder who put the stone cherubs there?

I wonder why I even care - though one thing is certain:

This is a place of delicate crafting –

of worms that churn soil cavorting with bees that stir air

of bronze hippos designing space with a correlated square…”

From Riddle, “Talking With Trees”

I also love the heart on the tree at the end of the book because it’s symbolic of everything these poems are about. I took the photo in an unexpected moment when I was walking with a friend in the forest while having a discussion about love. This tree with a white heart painted on it suddenly appeared before us. I remember her saying “Quick take a photo, take a photo…This is magic”. I think it was around then that I realized I needed to start writing about these experiences.

4. How does your book bridge the human and plant worlds?

I talked about doing research in the previous answer, and while taking photos was a big part of how I was processing information, there was also a lot of asking of questions and looking for answers. I began to look at the world in a more scientific way. I mentioned the rainbow earlier and the phenomena of light and color. I became very curious about natural phenomena, and much of what I learned found its way into the book. For example, I think it’s amusing how the spider that crept into “The Storm'' also brought me onto the island of Naxos, in Greece, for a brief visit with Ariadne - and all this while I was actually bailing water out of my garage and thinking about the healing properties of salt. It’s so mysterious and wonderful how our lives are about all of these worlds coexisting.

“…Spiders have eight legs; four for the directions, and four for the winds. It’s believed that the hinges of their webs are invisible letters that are as instructive as they are insignificant. I bet that if asked they could write novels about their point of view on things such as storms…”

From The Storm, “Talking With Trees”

I remember once hearing a Catholic priest speak about how science, magic, and mystery are all related in that they are deeper and deeper levels of reality. The deepest level is mystery, and it requires faith. These are the relationships that I explore in “The Storm” but also throughout the book.

5. Can you tell us about a particularly memorable experience or moment during the writing and creating process of "Talking With Trees"?

I’ve mentioned discovering the heart on the tree and dreaming about various characters like Ariadne or the lady of the lake, but the most memorable connection was with my actual garden - the one that surrounded the house where I was living with my family. Once I started seeing my garden in this vibrant way, I felt that it was speaking to me and informing me about very important parts of my life. In “Secret Gardens” I talk about ferns, vines, and daffodils, but I’m actually speaking about my family and friends, the tension and the harmony that exists between older and younger generations, personality types, and ways of being.

“...Just look at the lilac, there is no dilettantism here.

The petals always falling and opening, yet rooted –

concentric waves of perpetual ceremony

that takes the breath away…”

From Seeds, “Talking With Trees”

I remember literally crying as I wrote one of those poems. It became very emotional, and the images were moving me so deeply that I realized I really was talking with trees.

6. How do you hope readers will be inspired or impacted by reading your book?

I hope that these poems will give people joy. It’s one thing to be happy, but the deep joy that comes from making connections and feeling part of something that is so much greater than we can ever fully imagine is really something that endures and is far beyond happiness. I feel as though the book is an invitation to get outside and enjoy the broadening of horizons that nature offers so generously. There are so many surprises, and this is where the magic comes in. I didn’t know beforehand that the tam tams, daisies, and cool underground basement with the bubbles rising in the glass of fizzy water would be such a source of joy in the poem “South” - but that’s how it turned out, and so “South” became about feeling almost delirious :

“...The Sun has slithered into my veins

and never

have I ever felt so alive

as thisssss”

From South, “Talking With Trees”

7. Can you share with us any upcoming projects or works in progress that you're excited about?

I’m in the process of completing a new collection called “Tempo”. These poems and prose pieces are about the passage of time. Here, the changing seasons, traditional ballads and storytelling are sources of inspiration as they reflect the shifting moods within the soul.

I have a background in music and dance and I’m working more and more on connecting the newer writing to the sound, texture and feel of the words. It’s as if I’m experiencing nature in a slightly different, less whimsical, perhaps more visceral way with these newer pieces. I’m also working more with themes of conservation. I’ve had several of these poems published over the last year in various literary journals and I’ve begun putting them together in a collection. This is an extract from one of these newer poems:

“…Dragons shift shape with tides and seasons.

This one’s from New York Harbor but could be

from Singapore, Ann Arbor, as all of her kind

would be stars if the tides had drifted otherwise,

if we her children had watched out for her and

seen the sludge encrusted claws grow with

the urban sprawl and the leviathan’s roar…”

From Dragon, Querencia Anthology, 2022

In the meantime, I’ve gotten a commission from a friend and choreographer, Fran Spector Atkins, to write a poem about wildfires. The choreography will premiere next autumn and I’m also very excited about this project.

8. How do you see your poetry and the themes of your book fitting into the larger conversation about environmentalism and conservation?

I spoke earlier about the loss of connection with nature in this modern, industrialized and now, sometimes, virtual world. So, I believe we must renew the link with what I call “real” reality as often as we can. One of the first poems I wrote in “Talking With Trees” was “Rocks”. I remember, I had just had a long phone conversation with my then aging father about hopes, dreams and wishes. And I remember really connecting with him in that moment talking about the delicate tension between dreams and the need for them to be rooted in solid ground.

Much of the problem today is that industrialization and modern capitalism have brought us into a highly abstract and exploitative relationship with nature. It’s as if the dream has been built on many mistaken premises. So we are losing touch, not just with nature, but with ourselves and one another. The result is that now, as a society, we’re on a slippery slope.

As I answer this question there is pelting rain outside my window here in Northern California, where it never rains, and there’s usually a terrible problem of drought. But it has been raining almost non-stop for weeks and even though we know that this extreme weather is a result of global warming, we continue to fool ourselves about carrying on in the same old ways. When it comes to nature, it’s as if we don’t know if we’re coming or going anymore. Our society is so preoccupied with money that it has lost touch with its most precious capital - nature. I feel that this materialism has cut us off from who we really are as human beings.

So, writing is a way to help myself understand what’s going on and get back onto firmer footing. “Rocks” is about how reality is actually a dream, that by dreaming allows us to affect change:

“...The crypt, the well, the church

atop a mountain, suspended in the sky - rocks

the very substance of our dreams, real as the empty howl of night...”

From Rocks, “Talking With Trees”

It’s such a gift to be part of a creative tradition that’s having this conversation about preserving what’s most valuable to us and imagining the future in bright new ways.

9. How do you balance the stillness and rhythm in your poetry and how do you use it to convey your message?

This question is about the craft of writing and personal stylistic choices. I’m a bit of a minimalist and I love stillness, but I often begin by writing a rush of ideas onto the page. At first I tend to write by hand on paper because I like to have a more direct relationship to the words and to be able to see what I cross out, the arrows that I draw to other parts of the page, and the upside down words that I sometimes can’t even decipher any more. Once I have a big mess in front of me, I begin the “shaping” part. This is the point where I start over and really plant those seeds that will become the poem.

The stillness and rhythm you speak of makes me think of creating air and light when trimming roses. I love this stage because it’s a very playful step in which I begin to objectify what I’m writing, not just so that it makes sense, but so that it flows nicely, has a tone that I feel good about, looks a certain way on the page, fits in nicely with the other poems in my collection and yet has its own unique spirit.

Rhythm is about creating surprise and I feel that there’s a point in the writing, when thanks to the rhythm, the poem begins to write itself. It’s contradictory because I’m always searching for more empty space and yet there I am placing words onto the page. I suppose a successful work of art always explores tension in one way or another : empty and full, dark and light, moving and still.

“…But the butterfly tree is in the middle of this story and the point is

I’m still here with a flashlight looking for what’s at the start.

Actually, there’s something about how the Sun rose today

that sheds light on this part…”

From East, “Talking With Trees”

10. Can you tell us about any challenges you faced during the writing and publishing process and how you overcame them?

The biggest challenge was feeling alone in the beginning when I was first getting started. At first, this solitude seemed like a necessity, but I quickly felt that I also needed some feedback. I was lucky in that my high school English teacher, Meir Ribalow, from ages ago, and who I had stayed friends with over the years, agreed to read the first small batch of poems. He had become a published writer himself and he gave me the constructive criticism I needed. Right away he told me that the poems were unlike anything he’d ever seen before and explained why. This was important for me to hear because I had no idea if what I was writing would have any meaning for anyone other than myself. He also gave me a sense for what was stronger and weaker in the writing. I remember, for example, sending him “The River” and writing something like “They were in love”. He wrote back saying “Come on, you can do better than that!” It’s then that I wrote:

“The look in her eyes is so familiar that I wonder if she couldn’t be me. The feeling is such that I’m not sure if it’s a memory or a wish.”

From The River, “Talking With Trees”

There’s a radio recording of early versions of some of the poems read by Cynthia Adler on the New River Writers program on the Clocktower radio in NY. It was his radio program, and I was truly honored that he had my work read there. He was very ill at the time and I was grateful for all the thought and time he gave me before he passed away.

After that summer of writing most of the poems, I got back into the basic things of life. I was very busy teaching English and didn’t have much time to work on writing. It wasn’t until I came to California during the Covid lockdown period that I went back into those files, did more work on the poems and started sending them out. It was great to have that distance on the work after those years and then the surprise of getting published little by little. Of course, the publication of the full collection with Plants and Poetry gave me great satisfaction. It was the conclusion of a long process.

Writing is a lonely endeavor and it’s wonderful to be able to exchange, and also to find the time to work. Before, I used to always ”steal” time, but now I have a little more of it and I love being able to not feel hurried as I write and rewrite. Some poems come quickly and easily, but others take a lot of patience and perseverance. The fun for me is really in the challenge. It’s wonderful that the writing now exists outside myself and with more and more feedback from readers - the work has taken on a life of its own.

“...This is typical of cedars.

The roots tell of branches

which tell of shadows

which tell of light

and magic and seasons and ordinary people passing…”

The Cedar Tree, “Talking With Trees”

Even after all this time writing poetry, I still see it as a kind of dance - a dance with shadow and light - a dance of discovery and wonder.

“On with the dance! Let joy be unconfined…”

From Waterloo, Lord Byron

—

Want to check out “Talking With Trees” for yourself? Order here >>